Market timing and the importance of dollar-cost averaging

Josh Pigford

Time in the market is better than timing the market.

Why is this quote accurate? Why shouldn't you try to time the market? Let’s jump into the details here. We’ll start with the definition of market timing , show with data why it’s not such a good idea, and share a simple strategy to follow instead to maximize your returns.

What is market timing?

Market timing is the strategy of buying and selling financial instruments (usually stocks) by attempting to predict and forecast the future behavior of the market.

These predictions can be made based on different factors like:

- Prevailing economic conditions such as interest rates and inflation

- Political conditions and conflicts at the state, national and international level

- Fundamental analysis of the stock or its company (reading balance sheets and income statements)

- Technical analysis of chart patterns and other data

The problem with timing the market is that it doesn’t actually work. The generally accepted theory (The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), developed independently by Eugene F. Fama and Paul A. Samuelson) concludes that it is theoretically impossible to consistently get higher returns than the market.

Fama and Samuelson state that this is because there are millions of investors in the stock market and that stock prices react almost instantaneously to news and events. Profiting from inconsistencies and arbitrage is highly improbable.

According to the EMH, if an investor tries to time the market, it generally results in lower portfolio returns. Several investors, financial professionals, and academics believe that it is impossible to time the market and beating it for any significant amount of time is highly unlikely.

If you'd like to dive deeper into the topic of market timing, tune in to the Ask Maybe podcast episode on this very topic!

How can market timing hurt your stock portfolio?

Transaction costs: Frequently buying and selling securities will incur substantial fees in brokerage, commissions, and other transaction costs every year. A buy-and-hold strategy would not incur any transaction costs till you begin your withdrawals as you approach your goals.

Taxes: If you buy or sell securities that you have been holding for less than a year, which is a big part of market timing, then any profits you obtain are taxed as short-term capital gains (at your current income tax rates), which are generally higher than the tax on long term capital gains.

Active management: If you hire brokers or financial managers to act on your behalf and time the market, you’ll soon realize just how high their fees (also called expense ratios) are. Some may go up to even 1-2% of managed assets every year. 1-2% may not seem like much, but if we consider that the S&P 500 would give us an 8% return in the next ten years, the 2% management fee is 25% of the stock market’s total return. These percentage points are lost returns that will not compound further for you.

Opportunity cost: Opportunity cost, in simple terms, means that by performing a particular activity, you are not engaging in any of the other activities that you can complete in the same timeframe. In other words, if you choose to do one thing, you lose out on everything else you could be doing instead. You could instead use the time you spend on trying to time the market on activities that have a much more significant effect on your overall portfolio returns, such as:

- Rebalancing your portfolio

- Setting a target allocation to each asset class (stocks, bonds, real estate, gold, etc.)

- Reducing investment fees (fees compound over time as well) and

- Ensuring that you're adequately diversified.

- Difficulty in reentering: In trying to time the market, there is always the fear of missing out on subsequent gains and the danger of knowing when to reenter the market. In a simplified example, let’s say that you exited your equity positions when the S&P 500 was at 1000 points, and in a couple of days after you sold, the market has reached 1100 points. Psychologically, it is challenging to reenter the market at higher levels (1100 points), especially when you were invested even at lower levels (1000 points). Many investors miss out on years of gains due to this phenomenon.

Why even timing the market perfectly doesn't make a huge difference

So timing the market can really hurt you. But it can be worth it if you do it perfectly and make a killing, right? Well, no.

Let’s look at a quick story backed by data that shows that even if you manage to time the market consistently, the returns don't vary by a lot in the long run.

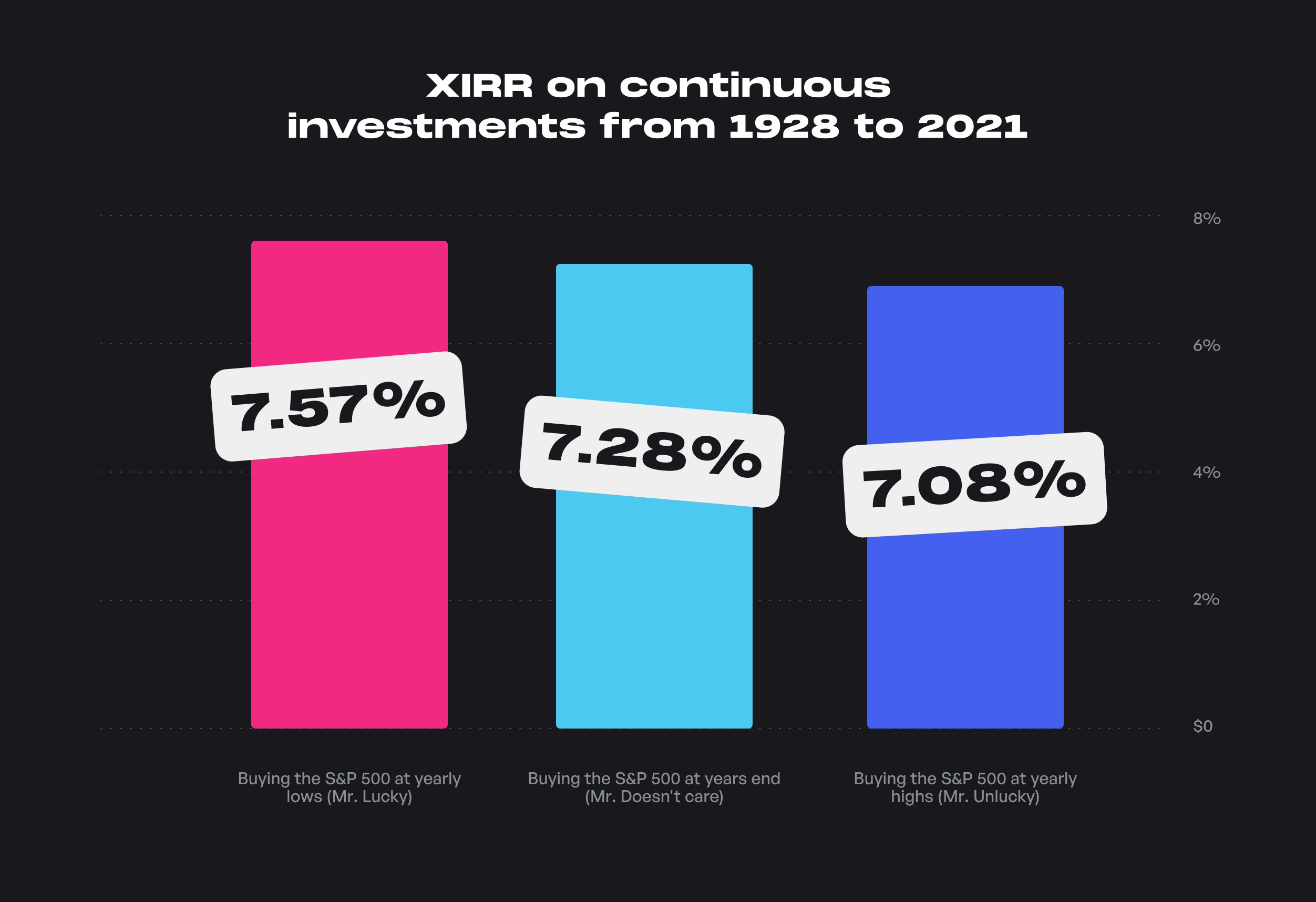

Let’s consider three investors:

- Mr. Lucky: He can time the market perfectly every year and buys the S&P 500 at yearly lows every year from 1928 to 2020.

- Mr. Doesn’t Care: He simply buys the S&P 500 at the end of the year, every year from 1928 to 2020.

- Mr. Unlucky: He is terrible at market timing and manages to buy at yearly highs every year from 1928 to 2020.

Take a look at each investor’s extended internal rate of return (XIRR) based on the recorded data of market highs and lows between 1928-2020:

(Source: Yahoo Finance)

Let’s look at those percentages more closely. The difference between Mr. Unlucky and Mr. Doesn’t Care is 0.2%. The difference between Mr. Doesn’t Care, and Mr. Lucky is 0.29%. And the difference between Mr. Unlucky and Mr. Lucky is 0.49%.

All three investors, including the investor who had perfect market timing every year for 92 years, ended up within a range of 0.5% of each other.

That’s not a big difference.

And that hypothetical situation doesn’t consider the realities of the market—for example, that it would be practically impossible to buy at the absolute top or bottom of the market every year for 92 years.

Let’s look at the same returns in terms of ROI. If all three investors invested $1000 every year (Total investment $94,000) from 1928 to 2021, this is what each investor’s portfolio would look like on a Return on Investment (ROI) basis:

| Strategy | ROI on $94,000 invested |

| Buying the S&P 500 at Yearly Lows (Mr. Lucky) | 144.9X |

| Buying the S&P 500 at Years End (Mr. Doesn't Care) | 116.5X |

| Buying the S&P 500 at Yearly Highs (Mr. Unlucky) | 100.1X |

Another caveat is that it is highly improbable that anyone can time the market consistently for even a few years (let alone for 94 years). The reverse is also true because it is very difficult to buy at market peaks year after year consistently (no one is that unlucky). Finally, you can minimize variability in portfolio returns further by investing every month instead of yearly.

Trying to time the market also incurs enormous fees in the form of brokerage and other transaction costs, taxes, and spreads between buying and selling prices (bid-ask spreads). Fees and taxes further reduce your portfolio returns as repeated buying and selling can incur substantial transaction costs and taxes.

The final point against trying to time the market is that most investors who try and time the market lose out on a huge percentage of market returns as emotions such as fear and greed make it difficult to reenter the market and result in panic buying/selling.

All this, combined with the fact that we are susceptible to a wide array of cognitive biases, shows that m arket timing does not help generate excess overall portfolio value/returns.

How to reliably grow your portfolio without timing the market

Now that we know that timing the market is not a factor that significantly affects the value of your portfolio let’s look at the factors that do. The significant drivers of portfolio returns (discussed in detail below) are diversification, rebalancing, indexing, dollar-cost averaging, and fees.

Diversification: Diversification is a strategy that involves adding a wide variety of asset classes, geographies, and financial instruments within your portfolio to reduce risks and exposure to one particular type. Properly diversifying your portfolio has several advantages, including lowering portfolio volatility, protecting you against market cycles, minimizing business and financial risk, and exposing you to different opportunities for return. Investing using ETFs like the Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund ETF (VT - Worldwide) or the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund ETF (VTI - US only stocks) can be a great way to achieve diversification in stocks.

Rebalancing: Rebalancing is the process of realigning the weights of the different asset classes in your portfolio based on your age and risk profile. Rebalancing can help you stick to your investment plan and ensure that your risk/reward ratio aligns with what you want it to be. It also makes sure that you sell part of the asset classes that have performed exceptionally well in the near past and buy asset classes that are beaten down to lower prices.

Dollar-cost averaging (DCA): DCA is an investment strategy wherein you invest a given sum of money into investment assets at regular time intervals. Dollar-cost averaging helps you stick to your investment plan as it removes the emotions out of investing. It also forces you to “Buy low and sell high” as you buy more units when markets are at low prices (undervalued) and buy less when markets are at peaks (overvalued).

Fees: As we saw when examining active management for market timing, fees like transaction costs, expense ratios, capital gains taxes, rebalancing costs, portfolio turnover costs, brokerage costs, and other trading costs can eat into your portfolio returns. Generally, guidelines like choosing index funds (low turnover and very low expense ratios) over actively managed funds (high turnover and high expense ratios), minimizing trading, and looking for tax-loss harvesting opportunities can help you reduce fees and keep a large part of the pie for yourself.

In simple terms, as an individual investor, the best way to maximize your portfolio returns without trying to time the market is to:

Diversify your portfolio across asset classes, countries, and financial instruments so that you don't get exposed to unsystematic risks. Diversifying adequately could prevent huge drawdowns in your portfolio when a particular asset class or country faces pressure.

Dollar-cost average (DCA) your investments over regular intervals of time. Following DCA means you automatically buy more shares when prices are low and buy fewer shares when prices are high. It also helps you navigate market volatility risks as you spread your investment over several time periods.

You can use almost 2/3rd of your portfolio returns to taxes and fees (transaction costs, expense ratios of mutual funds, taxes). Investing in low-cost, tax-efficient investment instruments like index funds can help you keep the bulk of the market returns to yourself.

Finally, setting a target allocation towards the various asset classes (stocks, bonds, real estate, gold, crypto, etc.) based on your age, risk appetite, and goals can improve your portfolio returns significantly. This allocation should change dynamically over time as you near your goals. Rebalancing helps you “Buy low and sell high” as you sell assets that have exceeded your target allocation (sell high) and buy assets that are below your target allocation (buy low).

Following the above principles and focusing the bulk of your attention on these pillars of investing will have a significant positive effect on your final portfolio value.

Subscribe to get the latest updates right in your inbox!